René Richard, Landscape Painter

par Pelletier, Esther

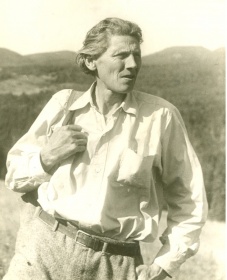

René Richard (1895–1982) is remembered as a remarkable and charming man who followed his passions. He spent the first half of his life in search of himself, surviving in the wilderness in harsh conditions. Richard’s father had emigrated from Switzerland to settle in Alberta, but Richard chose a nomadic existence among the Cree and Inuit in Canada’s North. All alone in these wide empty spaces, Richard became an artist. In 1927, he decided to study painting in Paris, where he met Canadian painter Clarence Gagnon. Upon his return to Canada in 1930, he again took up trapping, this time in Manitoba, before finally settling in Baie-Saint-Paul where he spent the rest of his life, painting the luminous, brightly-coloured landscapes of the Charlevoix region in a style halfway between traditional figurative painting and the emerging Quebec expressionism of the 1950s. Richard’s work shines a light on many aspects of Canada’s natural landscape and social history and represents a major contribution to Canadian art.

Article disponible en français : René Richard, peintre paysagiste

A Painter of Wide Open Spaces and Canada’s North

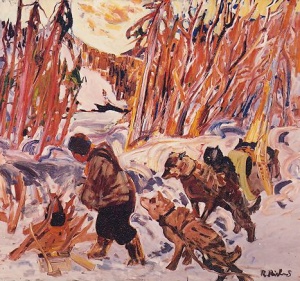

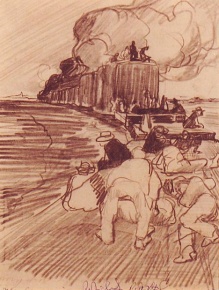

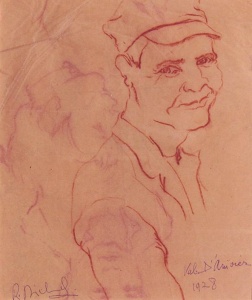

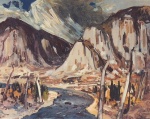

René Richard is without doubt one of the Canadian painters who best captured the North—its loneliness, rudimentary living conditions, and vast open spaces marked by the seasons. His prolific output stands as an impressive contribution to Canadian art: hundreds of works made up mostly of studies, drawings—a category that encompasses rough sketches, sanguine crayon, charcoal and pencil crayon as well as more detailed oil pochades and drawings in pencil crayon and felt pen—and small and large format oil paintings(NOTE 1).

No exhaustive catalogue raisonné of Richard’s work has yet been produced. Most works are housed in museums, government buildings, universities, private businesses and private collections. René Richard belongs among those Canadian artists who, like the Group of Seven(NOTE 2), dedicated themselves to depicting Canada’s wide open spaces and vast wilderness(NOTE 3).

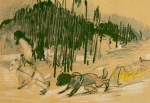

Whereas Canadian landscape paintings rarely depict human figures, Richard’s are often populated with the silhouettes of trappers, hunters and First Nations or Inuit people, as well as their sled dogs, tents, and huts. These silhouettes enter the landscape to bear witness to a way of life that, from adolescence into his forties, Richard shared with the trappers and aboriginal peoples of northern Alberta and Yukon, Nunavut and the Beaufort Sea area. Richard’s highly personal and somewhat expressionistic style conveys the struggle for human survival amidst the harsh northern environment of polar deserts, vast forests and rivers.

Early Life and Immigration: The Call of Nature

René Jeanrichard (later shortened to “Richard”) was only 11 when he began working at the family watch factory, where his father engraved pocket watches. A financial setback was behind Richard’s father’s abrupt decision to gather his sons and set off for Canada.

In those years the recently completed railway had opened up Canada for settlement and the government was working hard to attract European immigrants. The Prairies were promoted as “the last, best west” and free land was offered to those willing to homestead and work the land for three years(NOTE 4). This was the prevailing economic and social context when René Richard’s father landed with his three sons in Quebec City in 1909, before continuing westward to Edmonton the following year. Years later, the painter remembered those early days vividly: “We had loaded two wagons with everything a settler could need before leaving...The outfitters had us convinced that we would find a land of milk and honey. We set off for Cold Lake with four horses.”(NOTE 5) But Cold Lake proved disappointing. “We had to kiss our dreams of Eldorado goodbye…In the end, the ‘land rush’ had a lot in common with the gold rush of yore.”(NOTE 6)

Richard’s mother and four sisters eventually rejoined the men. The family had little choice but to work like slaves, “learning to live as settlers in the harshest, most demanding manner conceivable, without a moments rest either during the week or on Sunday.” Tiring of this ceaseless labour, the father finally gave up working the land.

The Trapper’s Life: An Apprenticeship in Solitude

Disenchanted with the settler life, Young René was far more interested by that of the First Nations. The tents on the lake shore, the birch bark canoes and horses—everything about the freedom of these nomadic hunters’ existence exerted an irresistible pull on the young man. “Maybe I was attracted to this untamed life as a reaction against my childhood, when I had to work in a watch factory after school.”

The clash of his childhood memories with “the freedom the Indians seemed to possess”(NOTE 7) inspired Richard to take to the woods with a friend named Charly. The pair spent entire days roaming the area on snowshoe, learning the valuable lessons this country of forests and lakes had to teach them about living in the wild. Richard crossed paths with people of all origins, accompanied by their dog teams, and repeatedly visited the aboriginal people camped along the lake, whose free way of life he admired. Finally, he decided to make this way of life his own.

For thirteen years, from 1913 to 1926, Richard learned the woodsman’s and trapper’s ways. With only a packsack, he travelled by snowshoe in winter and canoe in summer, criss-crossing northern Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba and even the Northwest Territories (now Nunavut). From Edmonton via Dawson, then a key stop for gold seekers en route to Alaska, he traveled down the Mackenzie River to the Beaufort Sea where he spent time with the Inuvialuit. He would, however, always return to Edmonton. It was there that he took his first drawing classes. Attracted by painting, he decided to leave for France to study at a reputed academy in Paris.

The Student in Paris: Nature Trumps Culture

In early 1927 Richard registered at Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where Quebec painters Kittie Bruneau and Jean-Paul Lemieux would also study, and took a room at a small hotel near Montparnasse. Little interested in the other students’ internecine squabbles over competing artistic currents, he was almost ready to pack it in and go home after four months spent mastering his technique. Fortunately, the Montreal painter Clarence Gagnon took Richard under his wing. Gagnon encouraged him to visit the museums and to draw and paint in the street. Falling back on his nomadic ways, Richard would also periodically pack his knapsack and set off to explore the countryside. In this way he traversed the Haute-Savoie region, the Côte-d'Azur, and even Switzerland, invariably returning to Paris with a great many drawings and paintings. Richard returned to Canada in 1930.

Once home, he discovered the familiar landscapes that occupied his dreams. He recalls spending his days “hanging around,” drawing the First Nations people on the neighbouring reserve. But the woodsman’s life was calling. In August 1930 Richard outfitted himself and headed for the wilderness. There he began drawing and painting like a man possessed. It was during this period of intense production that Richard came into his style. He still led the life of an outdoorsman, but paints and pencils were always now part of his gear. Unable to afford paper or canvas, he used rolls of butcher’s paper cut down to the desired size. He would even scrape the paint off previously painted boards, destroying old works to make way for new ones.

Richard hadn’t forgotten his long-standing dream of tackling the Churchill River; he successfully completed the perilous journey in 1933(NOTE 8). But the growing desire to paint would lead Richard to change his life. In 1938 he accepted his former mentor Clarence Gagnon’s invitation and moved to Montréal.

The Baie Saint-Paul Years: A Home, Artistic Maturity, and Recognition

Summer 1938 was a pivotal moment in Richard’s life. It began on Île d’Orléans, near Quebec City, where Richard helped Gagnon take inventory of the works of Horatio Walker, a recently deceased painter. Then the two visited Baie-Saint-Paul. They stayed with the Cimon family, who had often put up Gagnon on his earlier trips to paint the Charlevoix region. Then, through Gagnon’s friendship with the deputy hunting and fishing minister , René obtained a position as a game warden in the Parc de la Montagne de la Table at the foot of Mont Albert on the Gaspé Peninsula. This ideal seasonal job allowed Richard to earn a living through the fall while giving him time to paint in the open air. Unfortunately, a government decision eliminated the position and the following autumn found Richard unemployed. His savings were enough to get him back to Baie-Saint-Paul and the hospitable Cimon family. Richard loved both the town and its landscape; he could see why it was his friend Clarence Gagnon’s favourite place. He moved in with the Cimons, who greatly appreciated the odd jobs he did for the family. Blanche, the family daughter, was won over by his thoughtfulness and consideration. The two married in 1942, despite opposition from some relatives. Not everyone in town approved of this atheist outsider; rumour even had it that Richard was a Russian spy! Fortunately, everything settled down in the end.

From that point forward, René Richard dedicated himself to his art full-time. In 1943, he sold his first paintings and held his first exhibition at L’Art Français, a Montréal gallery. It was a smash: within a day and a half, every painting had been sold. Richard was able to pay back his debts. His work was then looked after by high profile galleries in Montreal (Klinkhoff) and Quebec City (Zanettin). René Bergeron in Chicoutimi also continued to show Richard’s work.

Richard’s reputation started growing. Artists, journalists and celebrities began knocking on his door. His routine was to receive guests over tea after his afternoon nap. His paintings were arranged for daylight viewing on the balcony of his large studio, adjoining the house. In 1948 and 1951 he joined expeditions to the Far North as a government consultant. These trips inspired the large-format northern landscapes Richard painted from memory between 1950 and 1965. In later years he chiefly produced scenes of the Charlevoix region where he made his home. He also became close friends with the authors Gabrielle Roy(NOTE 9) and Félix-Antoine Savard, among others. During Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip’s 1959 royal visit the couple was presented with a large René Richard painting depicting the Saguenay Fjord with two capes, Trinité and Éternité, in the background.

In 1973, at age 78, Richard was decorated with the Order of Canada. He travelled Europe with his wife Blanche and friends, including a visit to La Chaux-de-Fonds in his native Switzerland. Once home, he put aside painting and took up drawing again. Eye problems forced him to adopt new techniques, which he used to draw scenes of the Far North from memory with felt pens and colour pencils. During these years Richard divided his time between his garden, his friends and his drawing. In 1975, he illustrated Gabrielle Roy’s La montagne sécrète (translated as The Hidden Mountain)(NOTE 10) whose main character, Pierre Cadorai, was based on Richard. Another illustrated book, a new edition of Félix-Antoine Savard’s seminal novel Menaud, maître draveur(NOTE 11) (translated as both Boss of the River and Master of the River) came out in 1979. In 1980, Richard was made member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Two years later, one of his works depicting Nunavut, Great Slave Lake, was chosen by Canada Post for its 12 stamp themed series, “Canada Through the Eyes of its Artists.” René Richard died that same year, at age 86. His ashes were scattered from a helicopter over Parc des Laurentides near Baie-Saint-Paul, where a lake now bears his name.

René Richard will be remembered as a man with a zest for life, a man who realized his dream of capturing both the beauty and the violence of Canada’s arid, inhospitable, and often tumultuous wilderness, and lived to fulfill his dreams.

Commemorating an Artist’s Heritage

René Richard’s immense talent was widely recognized by the late 1960s. Several major exhibitions of his work were held both during his lifetime (Musée du Québec, 1967 and 1978) and posthumously (City of Montréal, 1986; Villa Bagatelle, Quebec City, 1990; Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, 1992–1993; Centre d'Art de Baie-Saint-Paul, 1993; and Domaine Cataraqui, Quebec City, 1996).

In 1978 Richard’s home and the Cimon property in Baie-Saint-Paul were designated cultural properties. Twelve years later, in 1990, the house was made into an interpretation centre dedicated to Richard’s life and work. The center also welcomes visiting artists in residence. Another monument to Richard’s memory is Espace René Richard in the J.A. DeSève Pavillion at Quebec City’s Laval University, where a large wooden sculpture of a canoe evokes Richard’s love of this traditional mode of transport. Richard’s peers have also paid tribute in various ways. In 1993, the sculptor Gérard Thériault made a bust of Richard, now housed at the René Richard library in Baie-Saint-Paul. Another bust sits atop a monument in the Saint Roch garden in Quebec City, along with monuments to fellow painters Alfred Pellan and Horatio Walker. And a documentary drama based on Richard’s life and work, Sur les pas de René Richard, was produced in 2003(NOTE 12).

In October 1980 Richard donated a sizeable collection of his work to Laval University: 46 paintings and sketches as well as a dozen drawings used to illustrate Menaud, Maître-draveur. On his death he bequeathed a second collection of 131 paintings and drawings to the university(NOTE 13). The René Richard foundation, created to commemorate the artist’s life and work, endows several scholarships awarded annually to Laval University visual arts students. In these myriad ways the legacy of this artist who so loved wide open spaces and freedom lives on.

Esther Pelletier

Professor, Laval University

NOTES

NOTE 1: Some of the oil paintings are as large as 130 cm X 112 cm. Some of the larger works were reproduced as limited edition lithographs signed by the artist.

NOTE 2: The Group of Seven was founded in Toronto in 1920 by seven modern landscape painters. They made the conscious decision to form a modern school of landscape painting and achieve recognition as such. Well known in Canada and worldwide, the Group of Seven was especially drawn to Georgian Bay, where members created large, ambitious landscapes of great formal beauty and harmony. The Group of Seven’s work married expressionist and decorative styles.

NOTE 3: Emily Carr (1871-1945), inspired by the nature of her native British Columbia, declared in 1912 that “Art is art, nature is nature, you cannot improve upon it. Pictures should be inspired by nature, but made in the soul of the artist; it is the soul of the individual that counts.” Carr was one of the few female landscape painters of her time, well known for her “expressionist” depictions of her province’s giant fir and cedar trees.

NOTE 4: Jacques Lacourcière, Jean Provencher and Denis Vaugeois, Canada–Québec 1534–2000. Quebec City: Septentrion, 2000, p. 386.

NOTE 5: René Richard, Ma vie passée. Montreal: Art Global, p. 13–14.

NOTE 8: See Jean-Guy Quenneville, René Richard, Le voyage d'un solitaire: Montreal, Trécarré, 1985.

NOTE 9: In 1957, Richard travelled as far as Mexico, crossing the United States by car to the Gulf of Mexico with his wife Blanche Cimon and Gabrielle Roy. See the correspondence of Gabrielle Roy in Mon cher grand fou, Lettres à Marcel Carbotte 1947-1979 (Montreal: Boréal, 2001, pp. 439–460).

NOTE 10: Roy, Gabrielle, La montagne secrète. Montréal: La Frégate, 1975 (limited edition art book). Roy’s novel is available in English as The Hidden Mountain, trans. Harry Binsse (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1974).

NOTE 11: Savard, Félix-Antoine, Menaud, maître-draveur. Montreal: La Frégate, 1979 (limited edition art book).

NOTE 12: Esther Pelletier, Sur les pas de René Richard (2003), a documentary drama produced by Nanoukfilms (Montreal) for ARTV, TV5 and BRAVO. Researched, scripted and directed by Esther Pelletier.

NOTE 13: Fifty or so of these works were shown from October 2–10, 1983 as part of National Universities Week. The official donation ceremony took place on Wednesday, October 5, 1983 in the Pierre Georges Roy room of the Quebec archives in the Louis Jacques Casault Pavillion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BERNIER, Robert, Un siècle de peinture au Québec, nature et paysage, Montréal, Éd. De L'Homme, Regards de nos plus grands peintres, 351 pages.

BOULIZON, Guy, Le paysage dans la peinture au Québec, Ottawa, Ed. Marcel Broquet, 1984.

LACOURCIÈRE, Jacques, PROVENCHER, Jean, VAUGEOIS, Denis, Canada-Québec 1534-2000, Québec, Septentrion, 2000, 591 pages.

OSTIGUY, Jean-René, Peinture et sculpture québécoises Structures et points forts (1670-1995), à compte d'auteur, Gatineau, 2009.

ROBERT, Guy, La peinture au Québec depuis ses origines, Saint-Adèle, Iconia, 1980.

SAVARD, Félix-Antoine, Menaud, maître-draveur, Montréal, Fidès, 1944.

Main works on René Richard (criticism, catalogues, novels, films)

Catalogue de l'exposition René-Richard, Musée du Québec, Québec, Ministère des Affaires culturelles, Éd. Marquis, 1978, 136 pages.

Catalogue de l'exposition René Richard 1895-1982, Centre d'exposition de Baie-Saint-Paul, 9 octobre 1993 au 30 janvier 1994, 24 pages.

DE JOUVENCOURT, Hugues, René Richard, Montréal, éditions La Frégate, 1978, 137 pages.

FONDATION RENÉ-RICHARD, Ville de Montréal, René Richard, Montréal, Fondation René-Richard, 1986, 80 pages.

PELLETIER, Esther, Sur les pas de René Richard, (2003), film documentaire-fiction, couleur et noir + blanc, 52 minutes, produit à Montréal par Nanoukfilms pour les télédiffuseurs ARTV, TV5, canal BRAVO ; recherche, scénario et réalisation de Esther Pelletier.

QUENNEVILLE, Jean-Claude, René Richard, Le voyage d'un solitaire, Montréal, Trécarré, 1985, 150 pages.

REVUE DE LA SOCIÉTÉ HISTORIQUE DE CHARLEVOIX, René Richard, Baie-Saint-Paul, numéro 16, juin 1993, 36 pages.

RICHARD, René, Ma vie passée, Montréal, Art Global, 1990, 153 pages.

ROY, Gabrielle, La montagne secrète, Montréal, Boréal, 1961, 186 pages.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Esther Pelletier phot

ographiée lors ... -

Esther Pelletier, niè

Esther Pelletier, niè

ce de René Rich... -

Femme assise, tête ap

Femme assise, tête ap

puyée sur une m... -

Forêt et cours d’eau

Forêt et cours d’eau

-

Gastronomie en forêt

Gastronomie en forêt

-

Homme assis sur un tr

Homme assis sur un tr

aîneau -

Homme près de chien t

Homme près de chien t

irant un traîne... -

Hommes dans la forêt

Hommes dans la forêt

-

Ile Vancouver 1960

Ile Vancouver 1960

-

Jeune homme couché

Jeune homme couché

-

L’étape. Scène du Nor

L’étape. Scène du Nor

d-Ouest, 1959... -

Le repas des draveurs

Le repas des draveurs

(Espace de Sèv...

-

Membres de l'équipe d

e tournage du d... -

Mon vieux camp sur le

Mon vieux camp sur le

68e Nord -

Montagnes et rivières

Montagnes et rivières

-

Pavillon de René Rich

Pavillon de René Rich

ard, 2 juin 197...

-

René Richard décoré d

René Richard décoré d

e l'Ordre du Ca... -

René Richard, 1969

René Richard, 1969

-

René Richard, 20 nove

René Richard, 20 nove

mbre 1969 -

René Richard, 9 septe

René Richard, 9 septe

mbre 1978

-

Territoire de Menaud,

Territoire de Menaud,

sans date -

Tournage du documenta

Tournage du documenta

ire-fiction «Su... -

Tournage du documenta

ire-fiction «Su... -

Tournage du documenta

ire-fiction «Su...

-

Tournage du documenta

ire-fiction «Su... -

Traîneau avec chiens

Traîneau avec chiens

et personnages -

Trappeurs et chien

Trappeurs et chien

-

Trappeurs et enfant (

Trappeurs et enfant (

Espace de Sève)...